Il RAPPORTO

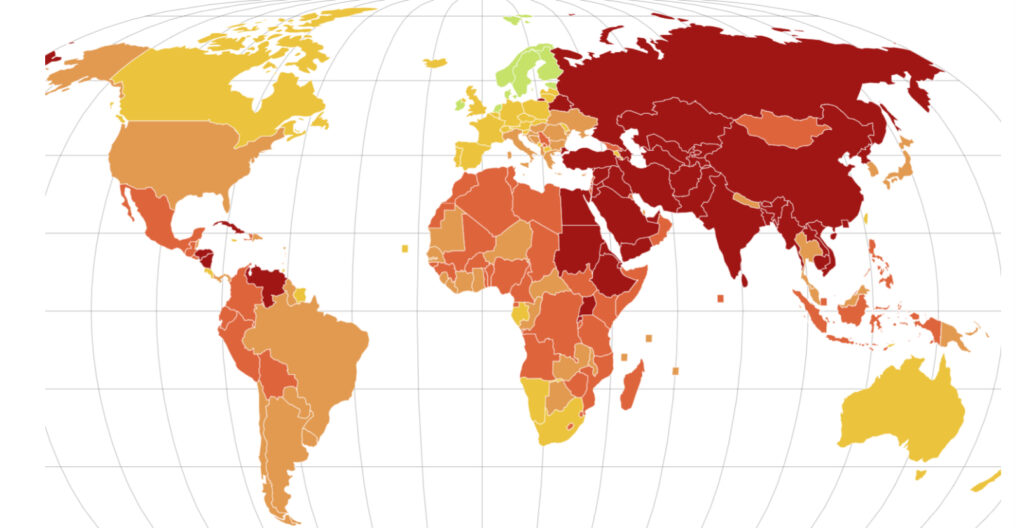

L’Italia passa da 46esima a 49esima nella classifica globale della libertà di stampa, stilata da Reporter senza frontiere (Rsf). Tre posizioni perse, che la condannano a essere il Paese con il risultato peggiore nell’Europa occidentale. Tre quarti dei 180 paesi presi in esame presentano comunque “condizioni problematiche e molto gravi”, “per la prima volta si evince una situazione difficile su scala mondiale”. La Norvegia si conferma al primo posto.

Classifica della libertà di stampa, l’Europa arretra

Benché l’Europa resti il continente più sicuro per i giornalisti, la situazione si sta deteriorando, complici le difficoltà economiche, le scelte degli Stati Uniti e la propaganda russa. L’Italia passa dal 46esimo al 49esimo posto, secondo Reporter senza frontiere L’informazione in Europa è sempre più in difficoltà. Sebbene il Vecchio Continente rimanga quello piazzato meglio nell’indice mondiale della libertà di stampa pubblicato venerdì dall’organizzazione non governativa Reporter senza frontiere, la situazione si sta deteriorando. Le difficoltà economicheminacciano le redazioni, soprattutto quelle indipendenti. Ma a pesare sono anche la fine degli finanziamenti in arrivo dagli Stati Uniti e il rafforzamento della propaganda russa: “Oggi Donald Trump rappresenta una minaccia tanto quanto Vladimir Putin”, spiega Pavol Szalai, responsabile della regione balcanica di Reporter senza frontiere.

Ai primi posti Norvegia, Estonia e Paesi Bassi. Problemi in Grecia

Norvegia, Estonia e Paesi Bassi dominano la classifica. Al contrario, Grecia, Serbia e Kosovo risultano essere i Paesi con i punteggi più bassi: sono rispettivamente 89esima, 96esima e 99esimo. All’interno dell’Unione europea, è proprio la nazione ellenica a risultare ultima. Secondo Szalai, “in Grecia, la libertà di stampa è minacciata dall’impunità sui crimini commessi contro i giornalisti. Mi riferisco all’assassinio del reporter Giorgos Karaivaz nel 2021. Finora c’è stato un solo processo e gli imputati sono stati assolti. Nel Paese si riscontra anche la più grande sorveglianza su giornalisti all’interno dell’Ue: più di dieci professionisti sono stati presi di mira attraverso il software di spionaggio Predator, che ha dato il nome all’ormai famoso Predatorgate“.

Male l’Italia: perde tre posizioni ed è al 49esimo posto

L’Ungheria, dove a più riprese si sono verificati colpi di mano da parte delle istituzioni, si colloca al 68esimo posto nella classifica sulla libertà di stampa. Reporter senza frontiere spiega che il governo di Budapest non lesina mezzi per controllare l’informazione: si calcola che ormai circa l’80 per cento delle redazioni sia controllato da persone vicine al primo ministro Viktor Orbán.

In Italia sono state perse tre posizioni rispetto all’anno precedente: nel 2024 la penisola risultava infatti 46esima, mentre oggi si è slittati al 49esimo posto. Secondo Reporter senza frontiere, la libertà di stampa ”continua a essere minacciata dalle organizzazioni mafiose, in particolare nelle regioni meridionali, ma anche da diversi gruppuscoli estremisti che esercitano violenze. I giornalisti lamentano anche tentativi della classe politica di ostacolare la libera informazione in materia giudiziaria“.

L’Europa resta il continente più sicuro per i giornalisti

Ne consegue che, sebbene l’Europa rimanga la macro-area più sicura per i mezzi d’informazione nel mondo, occorre rimanere vigili. “La libertà di stampa – prosegue Szalai – si è ulteriormente deteriorata in Europa. Ciò che osserviamo, allo stesso tempo, è che permane una distanza tra il Vecchio Continente e il resto del mondo: l’Europa rimane il luogo più sicuro per i giornalisti, nonostante tutti i problemi. E uno dei motivi per cui esiste questo divario è legato alla normativa in vigore a tutela della libertà di stampa: l’adozione l’anno scorso dello European Media Freedom Act da parte dell’Unione Europea, rappresenta un passo avanti storico”

La normativa mira a rafforzare l’indipendenza delle redazioni, a proteggere le fonti, a garantire una maggiore trasparenza sulle proprietà dei media e a proteggere i giornalisti dalle forme di spionaggio. Ma non tutti gli Stati membri la applicano allo stesso modo. EURONEWS 3.5.2025

RSF World Press Freedom Index 2025: economic fragility a leading threat to press freedom

Although physical attacks against journalists are the most visible violations of press freedom, economic pressure is also a major, more insidious problem. The economic indicator on the RSF World Press Freedom Index now stands at an unprecedented, critical low as its decline continued in 2025. As a result, the global state of press freedom is now classified as a “difficult situation” for the first time in the history of the Index.

At a time when press freedom is experiencing a worrying decline in many parts of the world, a major — yet often underestimated — factor is seriously weakening the media: economic pressure. Much of this is due to ownership concentration, pressure from advertisers and financial backers, and public aid that is restricted, absent or allocated in an opaque manner. The data measured by the RSF Index’s economic indicator clearly shows that today’s news media are caught between preserving their editorial independence and ensuring their economic survival.

“Guaranteeing freedom, independence and plurality in today’s media landscape requires stable and transparent financial conditions. Without economic independence, there can be no free press. When news media are financially strained, they are drawn into a race to attract audiences at the expense of quality reporting, and can fall prey to the oligarchs and public authorities who seek to exploit them. When journalists are impoverished, they no longer have the means to resist the enemies of the press — those who champion disinformation and propaganda. The media economy must urgently be restored to a state that is conducive to journalism and ensures the production of reliable information, which is inherently costly. Solutions exist and must be deployed on a large scale. The media’s financial independence is a necessary condition for ensuring free, trustworthy information that serves the public interest.”

Of the five main indicators that determine the World Press Freedom Index, the indicator measuring the financial conditions of journalism and economic pressure on the industry dragged down the world’s overall score in 2025.

The economic indicator in the 2025 RSF World Press Freedom Index is at its lowest point in history, and the global situation is now considered “difficult.”

The ongoing wave of media shutdowns

- According to data collected by RSF for the 2025 World Press Freedom Index, in 160 out of the 180 countries assessed, media outlets achieve financial stability “with difficulty” — or “not at all.”

- Worse, news outlets are shutting down due to economic hardship in nearly a third of countries globally. This is the case in the United States (57th, down 2 places) Tunisia (129th, down 11 places) and Argentina (87th, down 21 places).

- The situation in Palestine (163rd) is disastrous. In Gaza, the Israeli army has destroyed newsrooms, killed nearly 200 journalists and imposed a total blockade on the strip for over 18 months. In Haiti(112th, down 18 places), the lack of political stability has also plunged the media economy into chaos.

- Even relatively well-ranked countries such as South Africa (27th) and New Zealand (16th) are not immune to such challenges.

- Thirty-four countries stand out for the mass closures of their media outlets, which has led to the exile of journalists in recent years. This is especially true in Nicaragua (172nd, down 9 places), Belarus(166th), Iran (176th), Myanmar (169th), Sudan (156th), Azerbaijan(167th) and Afghanistan (175th), where economic difficulties compound the effects of political pressure.

The United States: leader of the economic depression

In the United States (57th, down 2 places), where the economic indicator has dropped by more than 14 points in two years, vast regions are turning into news deserts. Local journalism is bearing the brunt of the economic downturn: over 60 per cent of journalists and media experts surveyed by RSF in Arizona, Florida, Nevada and Pennsylvania agree that it is “difficult to earn a living wage as a journalist,” and 75 per cent believe that “the average media outlet struggles for economic viability.” The country’s 28-place drop in the social indicator reveals that the press operates in an increasingly hostile environment.

President Donald Trump’s second term has already intensified this trend as false economic pretexts are used to bring the press into line. This led to the abrupt end to funding for the US Agency for Global Media (USAGM), which affected several newsrooms — including Voice of America and Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty — and, as a result, over 400 million citizens worldwide were suddenly deprived of access to reliable information. Similarly, the freeze on funding for the US Agency for International Development (USAID) halted US international aid, throwing hundreds of news outlets into a critical state of economic instability and forcing some to shut down — particularly in Ukraine (62nd).

Media concentration and the dominance of online platforms

These serious funding cuts are an additional blow to a media economy already weakened by the dominance that tech giants such as Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon and Microsoft have over the dissemination of information. These largely unregulated platforms are absorbing an ever-growing share of advertising revenues that would usually support journalism. Total spending on advertising through social media reached 247.3 billion USD in 2024, a 14 per cent increase compared to 2023. These online platforms further hamper the information space by contributing to the spread of manipulated and misleading content, amplifying disinformation.

In addition to the loss of advertising revenue, which has severely disrupted and constrained the media economy, media ownership concentration is another key factor in the deterioration of the Index’s economic indicator and poses a serious threat to media plurality. Data from the Index shows that media ownership is highly concentrated in 46 countries and, in some cases, entirely controlled by the state.

This is evident in Russia (171st, down 9 places), where the press is dominated by the state or Kremlin-linked oligarchs, and in Hungary (68th), where the government stifles outlets critical of its policies through the unequal distribution of state advertising. It is also apparent in countries where “foreign influence” laws are used to repress independent journalism, such as Georgia (114th, down 11 places). In Tunisia (129th, down 11 places), Peru (130th) and Hong Kong (140th), where public subsidies are now directed toward pro-government media.

Even in highly ranked countries like Australia (29th), Canada (21st) and Czechia (10th), media concentration is cause for concern. In France(25th, down 4 places), a significant share of the national press is controlled by a few wealthy owners. This growing concentration restricts editorial diversity, increases the risk of self-censorship and raises serious concerns about newsrooms’ independence from the economic and political interests of their shareholders.

The Index’s survey shows that editorial interference is indeed compounding the problem. In over half of the countries and territories evaluated by the Index (92 out of 180), a majority of respondents reported that media owners “always” or “often” limited their outlet’s editorial independence. In Lebanon (132nd), India (151st), Armenia (34th) and Bulgaria (70th, down 11 places), many outlets owe their survival to conditional financing from individuals close to the political or business worlds. The majority of respondents in 21 countries, including Rwanda (146th), the United Arab Emirates (164th) and Vietnam (173rd), said media owners “always” interfered editorially.

Global state of press freedom is “difficult,” a historical first

For over ten years, the Index’s results have warned of a worldwide decline in press freedom. In 2025, a new low point emerged: the average score of all assessed countries fell below 55 points, falling into the category of a “difficult situation.” More than six out of ten countries (112 in total) saw their overall scores decline in the Index.

For the first time in the history of the Index, the conditions for practising journalism are “difficult” or “very serious” in over half of the world’s countries and satisfactory in fewer than one in four.

An increasingly red map

In 42 countries — harbouring over half of the world’s population — the situation is classified as “very serious.” In these zones, press freedom is entirely absent and practising journalism is particularly dangerous. This is the case in Palestine (163rd), where the Israeli army has been annihilating journalism for over 18 months, killing nearly 200 media professionals — including at least 43 murdered while working — and imposing a blackout on the besieged strip. Israel (112th) continued its decline in the Index, dropping 11 places.

Three East African countries — Uganda (143rd), Ethiopia (145th), and Rwanda (146th) — entered the “very serious” category this year. Hong Kong (140th) also moved into the red zone for the first time, and is now the same colour as China (178th, down 6 places), which has joined the bottom three countries, alongside North Korea (179th) and Eritrea (180th). In Central Asia, Kyrgyzstan (144th) and Kazakhstan (141st) have darkened the region. In the Middle East, Jordan (147th) plummeted 15 places, largely due to repressive legislation used against the press.

The Index by region: the gap widens between the European Union and other zones

The Middle East-North Africa region remains the most dangerous in the world for journalists, harbouring the mass destruction of journalism in Gaza by the Israeli army. Every country in the region is in a “difficult” or “very serious” press freedom situation, except Qatar (79th). The press is caught between crackdowns from authoritarian regimes and persistent economic precariousness. Tunisia (129th, down 11 places), the only North African country to fall this year, recorded the sharpest drop in the region’s economic indicator (down 7.97 points, down 30 places), due to a political crisis where independent outlets are under direct threat. Iran (176th), where journalists are gagged and all critical viewpoints are suppressed, remains near the bottom of the Index, alongside Syria (177th), which is still awaiting a profound transformation of its media landscape post-Bachar al-Assad.

Out of the 32 countries and territories in the Asia-Pacific region, 20 have seen their economic score decline in the 2025 World Press Freedom Index. The systemic media control in authoritarian regimes is often inspired by China’s propaganda model. China (178th) remains the world’s largest jail for journalists and reentered the bottom trio of the Index, coming just ahead of North Korea (179th). Meanwhile, the concentration of media ownership in the hands of influential groups linked to those in power — as seen in India(151st) — combined with growing economic pressures even in established democracies, means that press freedom in the region faces mounting repression and increasing uncertainty.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, press freedom is experiencing a worrying decline. Eritrea (180th) retained its position as the worst-ranking country in the Index. The economic score deteriorated in 80 per cent of the region’s countries. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo (133rd, down 10 places), where the economic indicator plummeted, the media landscape is hampered by persistent polarisation and repression in the east of the country. Similar patterns appeared in other conflict zones, such as Burkina Faso (105th, down 19 places), Sudan (156th, down 7 places), and Mali(199th, down 5 places). In these situations, newsrooms are forced to self-censor, close or go into exile. The hyper-concentration of media ownership in the hands of political figures or business elites without safeguards for editorial independence remains a recurring problem, as seen in Cameroon(131st), Nigeria (122nd, down 10) and Rwanda (146th). By contrast, Senegal (74th) moved up 20 places as its authorities launched economic reform initiatives, which still need to be implemented and carried out in a consultative manner.

In the Americas, the vast majority of countries (22 out of 28) have seen their economic indicators decline. In the United States (57th), Donald Trump’s second term as president has brought a troubling deterioration in press freedom. In Argentina (87th), President Javier Milei has stigmatised journalists and dismantled public media. Press freedom has been weakened in Peru (130th) and El Salvador (135th), undermined by propaganda and attacks on outlets critical of those in power. Mexico(124th), the most dangerous country for journalists in the region, has also seen a sharp decline in its economic score. Nicaragua (172nd) comes in last in the region and sits at the bottom of the Index, as the Ortega-Murillo regime has dismantled the independent media. In contrast, Brazil (63rd) has continued its recovery after the Bolsonaro era.

Europe still leads the regional rankings but is increasingly divided. The Eastern Europe- Central Asia (EEAC) region has experienced the steepest overall decline worldwide, while the European Union (EU)-Balkans zone has the highest overall score globally, and its gap with the rest of the world continues to grow. However, even the EU-Balkans zone is hurt by the media’s economic crisis, as seven in 10 countries (28 out of 40) have seen their economic score decline. What’s more, the implementation of the European Media Freedom Act (EMFA) — which could benefit the media economy — is still pending. The situation is worsening in Portugal(8th), Croatia (60th), and Kosovo (99th). Norway (1st) remains the only country in the world to enjoy a “good” rating across all five indicators of the Index. It held on to its top spot for the ninth consecutive year, increasing its lead over other countries. Estonia (2nd) moved up to second place, closely followed by the Netherlands (3rd), which overtook Sweden (4th) in the world’s top three.

La STAMPA e le intimidazioni mafiose – Commissione Parlamentare Antimafia